MT news

First Video Added to Moscow Times Web Site

The video, a 3 1/2-minute interview with Rose Gottemoeller, director of the Carnegie Moscow Center, examines the informal summit between Presidents Vladimir Putin and George W. Bush in Sochi on April 6. The video can be found on The Moscow Times' homepage, www.themoscowtimes.com.

Testimonials

"Congratulations to The Moscow Times from KPMG on your fifteenth anniversary. You are always readable, always interesting, always challenging. We sometimes don't agree with you – but you always make us think! The day would be the worse without you. Best wishes for many, many, more years constructive journalism."

KPMG Global Energy and Natural Resources Practice

Market Matters : Oil and Metals

Shine as RTS Breaks 2,100

The RTS, the country's benchmark stock

index, breached the 2,100 barrier for the first time this year, as oil and

metal stocks pulled away from the field.

Russia Investment Roadshow : Scenes From Last Year's

Forum

|

| |

| Tuesday, April 22, 2008 Updated at 22 April 2008 1:51 Moscow Time |

|

| The Moscow Times » Issue 3888 » Frontpage Top |

|

Moscow's Disabled Stuck in a Separate World22 April 2008By Svetlana Osadchuk / Staff WriterEvery morning, Vadim Voyevodin performed the same ritual: Bending over almost parallel to the ground, he lifted the baby onto his back, slung a towel around his son and knotted the edges around his chest. The little boy remained pressed close to his father's body throughout the day as he cleaned the house or cooked."I always dreamed of having a child, but I never imagined that this dream would come true at a time when I was single and handicapped," says Voyevodin, 59, who lives in a one-room apartment in northern Moscow with his son, now 16, who is also named Vadim. Voyevodin has not left the apartment in more than 10 years. Many disabled Muscovites, especially those with spinal problems, are effectively locked within the four walls of their homes -- doorways and elevators are rarely big enough for wheelchairs, and the Moscow metro and bus systems are not designed for people with disabilities. Voyevodin used to have a wheelchair, but it was broken several years ago. Now he moves around his apartment in an ordinary office chair equipped with wheels. "There are too many bureaucratic procedures to endure to get a new one for free. I have no courage to do it," he said. Under new rules introduced in 2006, all disabled people applying for federal benefits must have their disabilities verified by the state. Even amputees, paraplegics and those with genetic disorders must go through a lengthy process to confirm their disability and define the extent of it. They must obtain documentation from a variety of doctors as well as from their local department of social services, department of residential services, bureau of medical and social analysis and social security office. And naturally, visiting all these agencies requires standing in long lines. The process takes two to four months, and while the application is in process, the applicant has no right to any allowances or other privileges. Receiving the document that certifies the disability is only a temporary victory, however. The certification is only valid for a year, and then the process starts all over again. "They must think that my leg will grow next year while I secretly enjoy the privilege of moving around in a free wheelchair," said Mikhail Ruchnov, 42, who has been certified as belonging to the category of people with the most severe disabilities. In his annual report on the disabled in Russia, human rights ombudsman Vladimir Lukin noted that the number of complaints about bureaucracy had increased in recent years. The report also points out that those who are certified as disabled often qualify for equipment that they are unable to use. Some, but not all, Moscow apartment buildings have ramps designed for strollers, but these ramps are useless for wheelchairs. Additionally, many buildings have steps leading from the entrance to the elevator, and an October 2007 report from the social commission of the Vostochnoye Degunino district, where Voyevodin lives, notes that many buildings in that region have a gap of up to 4 centimeters between the elevator and the floor, making it impossible for a wheelchair to enter without being lifted, even if the elevator is big enough.

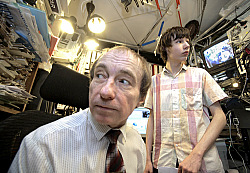

"My electric wheelchair weighs 110 kilograms. Who will lift it for me?" said Igor Lapin, 35, who lives alone. Lapin's comments are echoed by people all over Russia who post questions for President Vladimir Putin on the web site www.president.yandex.ru. "My son's wheelchair cannot fit through the doorway of our bathroom, so he cannot wash himself there," wrote Natalia from Murmansk. She added that her son's disabilities made it impossible for her to leave him alone and therefore she was unable to work. As the parent of a disabled child, she receives a monthly allowance from the state of 120 rubles ($5.13). The amount has not increased in 10 years. "If I hand my son over to the state, one month of caring for him in a group home would cost the state 15,000 rubles. It seems like the authorities are financially urging us to abandon our sick children," she wrote. Vadim Voyevodin says it was very hard to raise his son, who is now 16. At times, they only had bread and kefir to eat. Friends collected second-hand clothes and shoes for them. But family friend Vera Marushkina says Vadim was a great father, devoting himself completely to his son. Today, their one-room apartment looks like a control room, full of cords and monitors. The room serves as both a bedroom and the office of the Foundation for the Defense of the Rights of Disabled People, which Voyevodin founded in 1991. "The elder Vadim is a very forthcoming person, although life was cruel to him," said Vitaly Troyanovsky, a producer with the state television channel Kultura who included Voyevodin's story in one of his documentaries on pre-perestroika Soviet Union. A native of Moscow, Voyevodin moved to Karshi, Uzbekistan, in 1980 to work as a producer at a youth music club and theater. Voyevodin said his success in that position earned him the envy of the local Communist Party boss' son, Davron Gaipov, who considered himself the key figure in the local music scene. Shortly after a serious disagreement between the two, Voyevodin was arrested on suspicion of abuse of office and appropriation of club property. "They were false accusations. All the property was available in the club's storage. But Gaipov was a kind of god in the city," Voyevodin said. The case never went to court, but Voyevodin was held in a detention facility for almost four years. It was there on Aug. 25, 1985, that Interior Ministry soldiers beat him, fracturing his back. He returned to Moscow on a stretcher. No one was ever punished for the assault. It would be an overstatement to say the disabled lived well during Soviet era, but they did have some benefits, such as some free medication and an annual vacation at a sanatorium. This system of privileges continued until 2004, when a controversial law was passed that replaced these benefits with monthly cash payments. The law went into effect on Jan. 1, 2005. Another benefit involved a special car known as the Oka, an upgrade of a Soviet-era vehicle that was produced especially for the disabled. Certain categories of disabled people, including veterans and victims of Chernobyl, could receive an Oka for free, and all those who qualified for a wheelchair had the right to purchase an Oka at a 60 percent discount. This benefit was eliminated in 2005. Tatyana Morozova said she felt lucky to have an Oka, which gives her the opportunity to reach some small shops that are located beside the road.

"They sell stuff through the window. I drive really close to them and buy things like at a drive-through," she said. Tatyana Kozyreva, another wheelchair user who is also Voyevodin's friend, usually travels by metro. "I bring my wheelchair close to the stairs and wait for someone to help take me down," Kozyreva said. Sometimes she waits more than half an hour for someone to help her. She uses the same method to get out of the metro. Last year, the Moscow Department of Transportation introduced 30 special handicap-accessible buses, but this does not amount to much for a city with close to 1.5 million disabled citizens. Even if a wheelchair user manages to find one of the specially equipped buses, he will face more challenges once he reaches his destination. Curbs on most Moscow streets do not have gaps for wheelchairs, and few of the city's stores, hospitals, restaurants, theaters and museums have wheelchair ramps. Mayor Yury Luzhkov called the center of Moscow a wilderness for the disabled because of its lack of accessibility, ITAR-Tass reported. Voyevodin has always fought to improve life for the disabled and has become even more committed since establishing his foundation. Through the foundation, he pressed for the installation of banisters at the entrance to Morozova's apartment building in northeastern Moscow. People in wheelchairs are rarely able to defend their rights in court simply because they cannot get there. Laws oblige court officials to visit disabled people with pending cases, but usually they try the cases in absentia. In 2005, Voyevodin filed a lawsuit seeking 32,000 rubles he claimed he was overcharged for electricity, but in his absence, the Timiryazevsky District Court in Moscow ruled in favor of the utilities provider, Mosenergo. While Voyevodin has solved problems for many of his friends, he has been unable to win any of these small victories for himself. His apartment features none of the special equipment for disabled people that can be found in Western countries. Vladimir Doronin, an engineer with Tekhma, a company that specializes in installing equipment for disabled people, said measurements were taken to install a special lift for the tub in Voyevodin's apartment, but the addition has not been made. "We can do it, but somebody has to pay for this. It would cost about 50,000 rubles to equip his apartment with everything he needs," Doronin said. Even if the state has verified an individual's disability and determined what kind of technical aids may be needed, these aids, such as the kind of lift Doronin wants to install for Voyevodin, are not included in the state program for aid to the disabled, said Lin Nguen, a lawyer with the nongovernmental organization Perspektiva. Today, the younger Vadim tries to help his father as much as he can. They enjoy each other's company and avoid talking about Vadim's mother, who was a nurse at one of Moscow's rehabilitation hospitals and disappeared from their lives when he was an infant. Voyevodin likes to talk about his passion for music and the theater and the artist friends he used to have. Many of his old friends tried to keep in touch after he became disabled, but most of them have fallen away over the years. In Russia, the disabled simply live in a world apart. | ||||||||||

Currency Exchange

USD/RUR - 23.5

EUR/RUR - 37.1

Weather

Most Popular Stories

2. The Next Collapse Will Be Russia's Last

3. Putin Warms to Separatist Provinces

4. Americans Are Not Stoopid

5. Security and a NATO Deal for Putin

Archive

| « 2008 |

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

| 31 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

Columnists

Why Moscow

Doesn't Have a Lot of Friends

By Georgy

Bovt

How to purge

those strange, servile bums

By Michele A.

Berdy

Those

Ukrainian, Iranian NATO Blues

By Richard

Lourie

A Shift in

Authority

By Konstantin

Sonin

Making a

Killing by Selling Weapons

By Yulia

Latynina

The Lovely

Smell of U.S. Stagnation

By Alexei

Bayer

Military

Service in Absentia

By Alexander

Golts

A Perilous

Tale of 2 Lions and Lots of Jackals

By

Alexei Pankin

Green With

NATO Envy

By Boris

Kagarlitsky